Like Whooping Cranes, Peregrine Falcons have shown us how endangered species can come back from the brink of extinction in response to conservation efforts. Whereas Whooping Cranes almost disappeared due to over-hunting and habitat loss, Peregrines suffered poisoning by the pesticide DDT that made them unable to breed successfully. As a result, one of the most widespread animals in the world completely vanished from many parts of North America. The Endangered Species Act came to the rescue, the American and Canadian governments banned DDT, and biologists began widespread efforts to reintroduce Peregrines to the wild, using captive-bred birds, including in Nebraska.

Famous for being among the fastest animals in the world, Peregrines can reach diving speeds of over 200 miles per hour! They are also champion long-distance migrants, with some birds traveling 10,000 or more miles round-trip between their breeding and wintering grounds. While Peregrines have been extensively studied on their breeding grounds in North America, data on their wintering destinations and ecology in South America are few and far between. Recently Crane Trust scientists were contacted by Peruvian colleagues regarding Peregrine Falcons located on the coast of Peru, including a captive-bred bird banded and released in Nebraska.

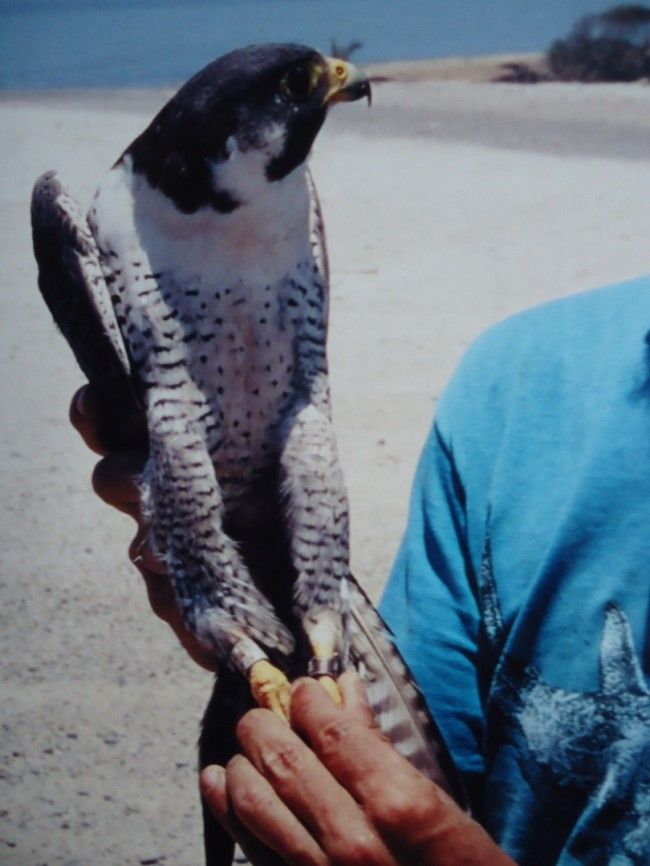

Crane Trust scientists are now working with partners to use band encounter data to better understand the links between Peregrines’ breeding and wintering grounds, or migratory connectivity. The falcon in this photo flew 4000 miles from where he was hatched and banded in Nebraska to where he was captured and re-released on his wintering grounds in Peru. To our knowledge, this is the longest known migration of any captive-bred Peregrine, and the first report of a USA-breeding bird wintering in Peru; most records of wintering Peregrines in South America are from Canada. With a name derived from the Latin word for “pilgrim,” Peregrines are great travelers but are also highly philopatric, meaning that they show high rates of return to their breeding and wintering territories. True to his nature, the Peregrine pictured here in Peru returned to Nebraska in subsequent years to nest successfully.

Like Sandhill Cranes, Peregrines have shown tremendous resilience to the ways humans have transformed the landscapes of North America. Whereas many grassland birds have declined in response to conversion of their native habitat to row crops like corn, Sandhill Cranes have benefited from the waste corn scattered in the fields surrounding the Platte River in the spring. While many native North American birds have disappeared from urban areas, Peregrines have increasingly moved into cities, nesting on skyscrapers and feasting on pigeons. In return for this opportunism, populations of both species have increased in the last decades.

Keep your eyes out for Peregrines on the prairie!