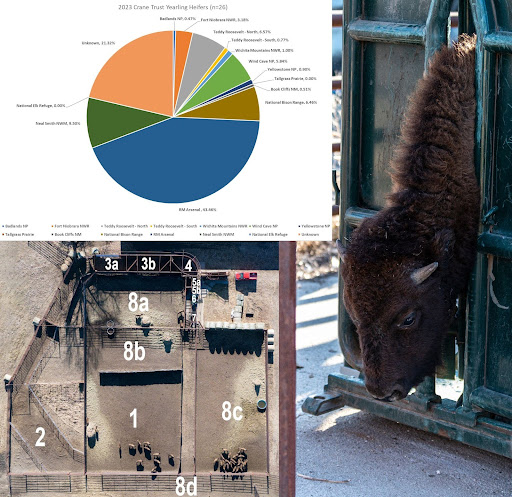

Top left: Pie chart displaying the genetics of our 2023 yearling heifers.

Bottom left: Labeled bison working setup:

1-Holding pen

2-Funneling alley

3-Separation Alley

4-Swing tub

5-Lead-Up Alley

6-Squeeze chute

7-Separation chute

8-Post Working Pens

Right: Yearling bison in the squeeze chute.

Before we stampede into this blog, I would like to say thank you to everyone involved! Working our bison takes a lot of teamwork and trust. Employees from every department of the Crane Trust, and recruited individuals come together to get this job done. Most people involved have years of experience and bring a great deal of expertise to working our bison. Without everyone involved, we could not have completed this daunting task.

At the Crane Trust, we work our plains bison (Latin name Bison bison bison) annually. Since acquiring about 41 bison in 2015 our herd has grown to 170 individuals. We collect tail hair DNA for genetic testing, collect feces to monitor their parasite loads, give them identification tags, take their weight, score their body condition, and sort them into groups while working. All of this work is done to achieve five main goals.

“Goal 1: Improve ecosystem structure and function by reintroducing bison as a keystone species to enhance the diversity of the native prairie and wet meadow ecosystem along the Platte River.

Goal 2: Support the genetic recovery of bison in North America and provide a model of genetic diversity management.

Goal 3: Maintain bison well-being with limited human intervention and develop standard operating procedures to monitor bison health while maintaining the safety of bison and bison handlers.

Goal 4: Improve outreach and education efforts, contributing to the cultural significance of bison by impressing the story of their extinction and recovery, and the need to conserve native habitats similarly to visitors and the community.

Goal 5: Develop strategies of long-term economic sustainability for the bison program using ecologically sound culling decisions.”

These goals and a lot of what I write come from Josh Wiese’s A Comprehensive Bison Management and Research Plan for the Crane Trust (unl.edu). This publication is available on the publications portion of our website and its link is up above if you would like an in-depth look at our bison program.

Low-Stress

You might ask yourself, how do you move an animal as large and dangerous as a bison through a system of gates and alleyways, while maintaining goal 3? Well, it is not a simple process, but we keep it low-stress. This is done using their flight zones (areas surrounding an animal that when approached, will trigger escape behavior) and the minimum stimulus needed to move them through our corral system. Sometimes even the slightest movements by the handlers, such as slowly wiggling their hand, can provide enough motivation for the bison to continue on their way. In addition to this, our team will move our herd into the corral throughout the year with the use of minerals, salt blocks, and watering stations to make it a normal occurrence with zero negative feedback. This allows us to guide them into the corral with ease. From here we move them into a more specific portion of the corral, called the holding pen, and we are ready to start working.

Process

Tim Smith and Carson Schultz (TNC) drove small groups of 4-8 bison from their holding pen (1) down our funneling alley (2) where Dave Baasch closed a gate behind them. Then Adam Driver closed the next gate confining the bison into the first section of the separation alley (3). At the second section of the separation alley (4) and the swing tub (5) Bruce Winter and Stu Dethloff separated bison in preparation for sending them through the lead-up alley (6). The goal is to have one bison given access to the squeeze at a time, which was Amy Sandeen and Mallory Beckmann’s job at the lead-up alley gates (6 and 7). Gary Sitzman controlled the squeeze chute (8). Once he safely restricted the bisons’ movement, Mallory, Megan Soldatke, Bethany Ostrom, and I took fecal samples, genetic samples, weight measurements, and body condition scores (appearance of leanness). At the same time, Josh Wiese was tagging each untagged individual and Bethany was keeping track of what tests needed to be done on each animal. A normal tag with a number and an electric identification tag is given to our bison. As I am sure you have guessed, these tags are used to keep track of each bison’s identity in the field as we manage our metapopulations, run our genetics program, and sell yearlings. Once all this was done, Josh would change gates and adjust our separation chute before release into their appropriate pens. This way we could sort individuals based on their predestined future. We separated our bison into 4 main groups: 1) breeder bulls, 2) yearling bulls, 3) yearling heifers (females), and 4) animals staying at the Trust. Everyone had specific jobs but would jump in anywhere additional help was needed.

In case you were wondering, we separate our animals like this so individuals are sorted by sex and age and are ready for transport after our sale on January first. This year we are in the process of selling 39 individuals to share the genetic diversity we have helped create and sustain our bison program (goals 2 and 5). Two are two-year-old bulls and 37 are yearling bulls and heifers. So now that you understand the process of bison working more, let’s talk about our samples.

Fecal Samples, Weight, and Body Condition Scoring

Fecal samples are taken to monitor parasite loads. They are allowing us to watch for any health declines requiring us to give anti-parasite medicines (spray-on dermal and oral dewormers). Luckily, our data has suggested that bison are less susceptible to high parasite loads as they reach about 2 years of age, so we do not have to intervene unless there is good reason to do so. Intervention is only needed in the occurrence of weight reduction, reproductive difficulties, and possible death, which we haven’t encountered yet. Weight and body condition scores are recorded during working to check for a correlation between lower weight and higher parasite loads. Body condition scoring requires looking at the ribs, spine, hip bone, tail head, and hump area of an individual and scoring it from one to five. The more full these areas are the higher the score. Below are links to explore fecal sampling and body condition scoring in more detail.

1) A Crane Trust blog on fecal sampling procedure A Bison Patty Party In The Lab (cranetrust.org).

2) A National Bison Association document on how to score bison What’s the Score: Bison – Body Condition Scoring (BCS) Guide (bisoncentral.com).

We collect fecal samples twice during the growing season to monitor our older animals as well but without the ability to measure weights and accurately score body conditions. We still have questions regarding our bison and parasites giving us reasons to continue monitoring parasites, including; Do reproducing females (reproducing female bison) with calves have more or less parasites? What do a calve’s parasite loads look like in comparison to their mothers? Do they correlate? Should we give certain calves or all calves an oral dewormer while working them? And many more

DNA Sampling and Herd Genetics

DNA tail hair samples are pulled to understand breeding dynamics, social hierarchies within the herd, and determine when animals should be moved to or from the Crane Trust to increase our herd’s genetic diversity. Bulls are moved to increase genetic diversity or to prevent inbreeding. We move bulls because it is a simple and effective way to increase diversity in our herd. Replacing a couple of bulls instead of ten or more genetically similar and reproducing females also makes sense financially. Each calf is about 50% mom and 50% dad, so within two breeding seasons one dominant bull can produce around 90 offspring. By that time he has done his job of spreading new genetics in our herd and can move on. When you need more diversity in the herd you get rid of the bulls with similar genetics, because we cannot control who the dominant breeding male is and let bulls from other dissimilar populations spread their genetics.

At the beginning of this blog, you can see a pie chart of our 2023 heifers’ genetic makeup. This pie chart shows you where our heifers’ genes came from, displaying over 40% of their genes coming from RM Arsenal. This is because 2023’s dominant breeding bull was close to 100% RM Arsenal.

Our bison genetics program brings genes back together and is aimed at providing bison breeding stock that is genetically diverse and resilient to disease, climate change, drought, and can inhabit a variety of habitats across the great plains, even in the Intermountain West. We disseminate our bison to other conservation-oriented bison programs through a yearly sale of our yearlings who are naturally weaned from their mothers and are about 20 months old. This not only helps the greater bison community, but keeps our herd at a sustainable carrying capacity, and is the most ethical way to keep bison social structure intact at the Crane Trust.

Main Purpose

The three main actions that help us achieve our mission are intertwined with having bison on the landscape. Land management, scientific research, and education help us protect and maintain the physical, hydrological, and biological integrity of the Big Bend area of the Platte River so that it continues to function as a life support system for whooping cranes, sandhill cranes, and other migratory bird species. Bison help with land management by providing an additional grazing option that is different from cows. They graze in a way that creates different heights of grass in the prairie and alternative patchy vegetation structure, this grazing style produces habitat for species relying on different grass heights and forb percentages. In areas of intense grazing wildflowers and forbs increase in number. Wallowing and hoof action rejuvenate the prairie’s plant communities as well. The most notable reason to have bison for land management is that they evolved with the prairie and created a more natural system of grazing and resting. Bison provide us with many scientific research avenues. Just by having bison on the landscape, there are unlimited research questions to answer. The scientific research done here positively impacts the bison population as a whole. Providing new insights on how to take care of bison. Our parasite monitoring research is one example. Bison create productive learning environments by inspiring people from all walks of life to be curious and experience the beauty of our prairies, making education efforts engaging and awe-provoking. Sandhill cranes are the main way we get people interested in learning about our mission and the importance of our prairie and wet meadows, but they are only here a small portion of the year. For the remainder of the year, bison are a pivotal inspiration for those visiting to learn about and experience the Crane Trust.

Thank you for reading this blog on bison working! I hope you enjoyed learning about how we take care of our metapopulations at the Crane Trust.

See you in the next blog!

Matt Urbanski,

Saunders Conservation Fellow

murbanski@cranetrust.org