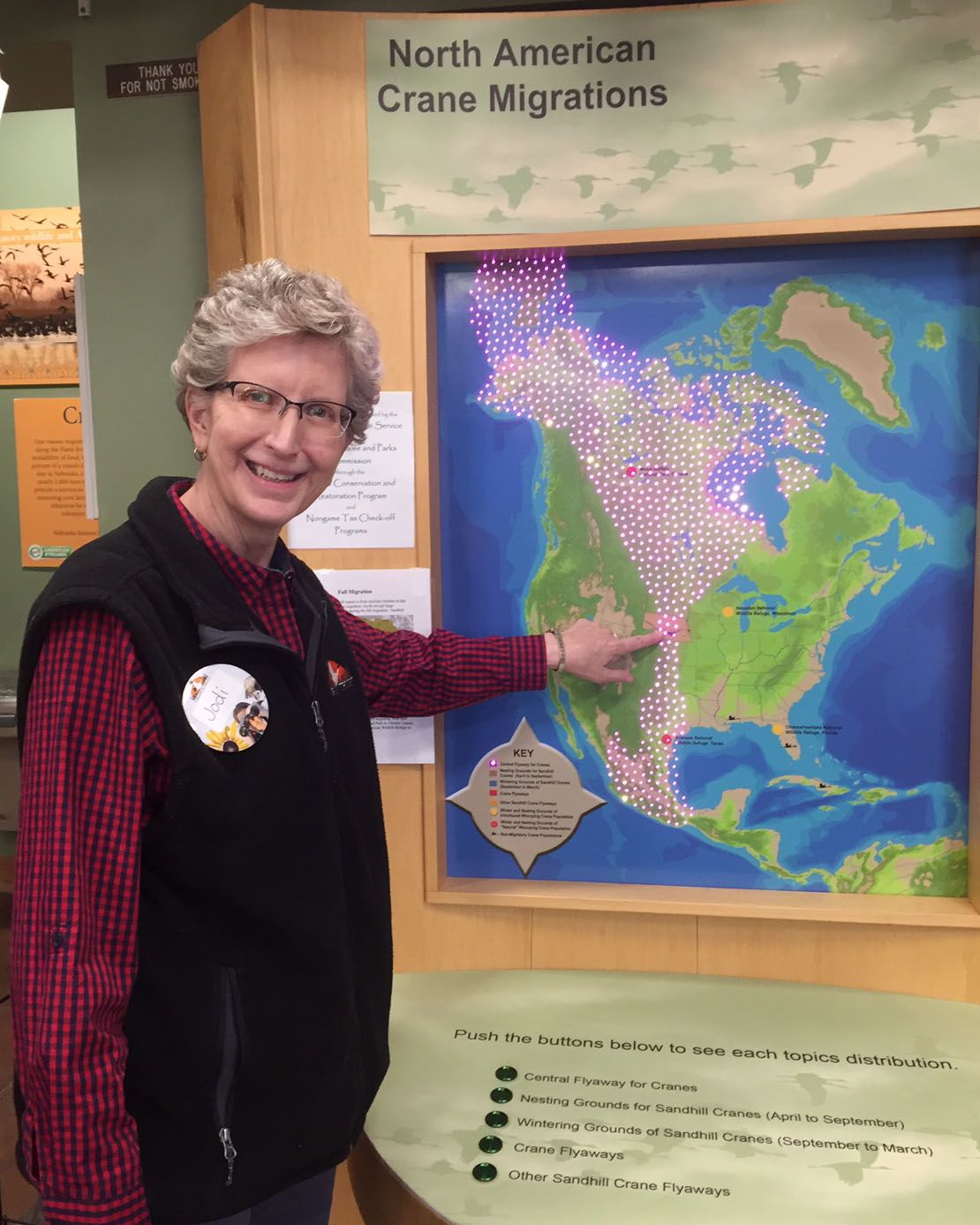

How did the Sandhill Crane get its name? Do people feed the cranes? Why do cranes dance? Fielding these and countless other crane questions is what Crane Trust volunteer Jodi Fegley does every day she spends at our Nature and Visitor Center. One of the most common questions people ask is whether the farmers or the government feed the cranes when they come through on migration. Although an estimated 90% of Sandhill Cranes’ food during their Platte River stopover consists of corn, this is not food that has been intentionally provided by farmers or the government, but rather “waste grain” left in the fields after the annual harvest. Much of this corn is knocked off the ears during the growing season by ferocious winds that periodically sweep through the Great Plains – one reason why wind might be a crane’s best friend. Another is that the cranes test the winds blowing from the south when the time comes to travel on the next stage of their migration, so they can ride them north toward their summer breeding grounds.

“People come here to learn,” Jodi explains; “I love it when people ask questions and I don’t know the answer – then I get to do research!” She recently sought to identify which crane species performs the longest migration; it turns out the winner is our very own Sandhill Crane, specifically members of the Arctic-breeding subspecies (Lesser Sandhill Crane) that travel up to 5000 miles via the Central Flyway. Because of cranes’ abundance on the Platte River, many people assume their name refers to the Sandhills ecosystem of Nebraska; on a recent visit, however, Paul Johnsgard explained that their name may, in fact, refer to the Sandhills ecosystem of Florida, closer to where European ornithologists first encountered this species in eastern North America. Jodi relays such facts and details to thousands of visitors, noting: “You can’t care about something you don’t know about.” Many people ask about the biggest cause of crane mortality and are surprised to learn that in Nebraska, where all cranes are protected from hunting, it’s collisions with powerlines. Some good news is that Kansas and Nebraska utility companies have made efforts to identify and mark particular powerlines that pose the greatest risk to birds, and this may inspire other states to follow their lead of bird diverter installations for the benefit of our avian friends.

Growing up, Jodi never learned about cranes – she has developed all of her expertise through many years of interacting with visitors, for many of whom she is the face of the Crane Trust. Now, students from preschool to university levels come to the Crane Trust, which Jodi uses as a crucial opportunity to get them to know and care about cranes and understand the importance of the Platte River ecosystem. This year, due to the catastrophic flooding that hit in March, she received many questions about how the flooding affected the birds. Why cranes dance is another frequent subject of questions and fascination. Given the critical importance of the 80 mile stretch of the Platte River to cranes, Jodi reports, many people are shocked to learn that no part of this area is protected via a national park or other government protected area. Some ask where they can get the best views of cranes: from a bridge, in a blind, or in the fields? While many people like to get as close as they can, Jodi notes, she prefers to stand back and see the birds gathering in the vastness of the whole sky.