Welcome back!

In my last blog post I talked about my favorite migratory group of birds, but this week I could not pass up the opportunity to talk about not only the tallest bird in North America, but one of the rarest as well…the Whooping Crane (Grus americana)!

Did you know after more than a century of habitat loss and continuous hunting the migratory Whooping Crane population was thought to be extinct? However, in 1941 15 Whooping Cranes were discovered in a wetland within the Wood Buffalo National Park in northern Alberta, Canada. These 15 migrants and an additional 6 non-migratory individuals in Louisiana made up the last two populations of Whooping Cranes. Unfortunately, in 1950 only one Whooping Crane remained in the Louisiana flock. In order to try and save this remaining crane, U.S. Fish and Wildlife captured the bird and transported it to wintering grounds at Aransas National Wildlife Refuge in Texas, in hopes it would join the migratory population. For 60 years, Whooping Cranes were absent from Louisiana’s landscape. However, in 2011, Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries and partners began a reintroduction project, releasing 10 juvenile cranes at White Lake Wetlands Conservation Area. There are now almost 70 individuals residing in Louisiana! Additional reintroduction efforts have also occurred in Wisconsin and Florida with the help of captive breeding programs.

The migratory population, known as the Aransas-Wood Buffalo flock, has slowly increased over the last few decades as well and has now surpassed 500 individuals! The increase in numbers is the result of intensive conservation efforts brought forth by state, federal, non-profit, and private organizations over the last 80 years. Nevertheless, environmental and anthropogenic factors, such as continuous loss of habitat, altered wetland conditions, climate change, and collisions with power lines, have complicated population recovery.

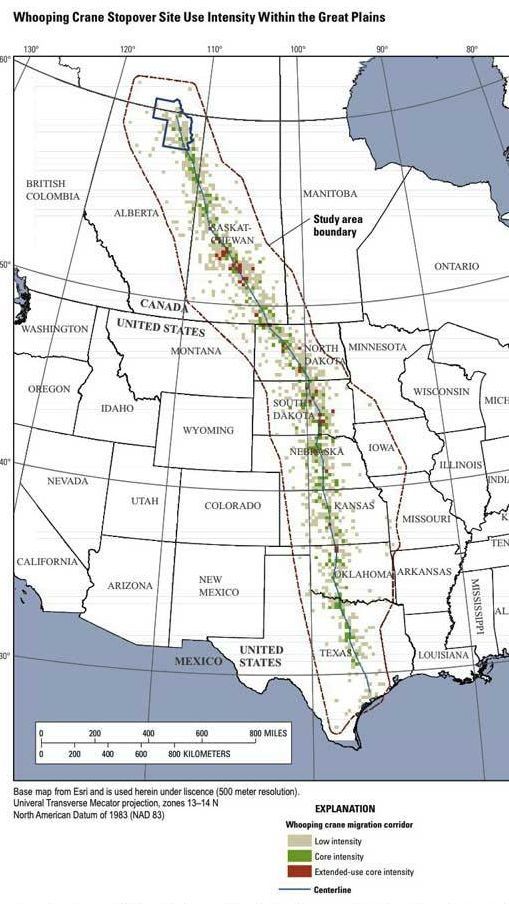

The Aransas-Wood Buffalo Whooping Crane population spends the winter (November to March) along the Gulf coast of Texas until spring migration (late March to late April) where they fly to Wood Buffalo National Park in northern Canada to breed (May to September). Once breeding season has passed and winter is upon them, the cranes will migrate back to the coast of Texas and the cycle will repeat. While their migration route is long (about 2,500 miles), it is quite narrow (less than 300 miles wide). In order to successfully complete their migration, Whooping Cranes rest and feed at stopover sites, including areas along the Platte River. A variety of habitats are used as stopover sites, such as wet meadows, sloughs, crop fields, and shallow waters on the river.

(Map from Whooping Crane Stopover Site Use Intensity Within the Great Plains by Pearse et al. 2015)

In previous posts (Disking the Platte River and Things are really heating up!), I talk about ways in which the Crane Trust manages their properties to continue protecting and maintaining essential habitat for migratory bird species. What I have yet to discuss is how the Crane Trust studies Whooping Crane behavior to determine beneficial management for their habitat in the first place?

To answer this question, a Whooping Crane specific study titled “Whooping Crane Diurnal Behavior and Natural History during Migration in south-central Nebraska” was established in October 2019 by Caven et al. The objective of the study is to collect behavioral data that will allow the Crane Trust to link behaviors to habitats Whooping Cranes are utilizing. This monitoring will help the Crane Trust determine what value different habitats provide, as well as how behavior varies across these habitat types. The study uses an “instantaneous scan sampling” approach. This means that Whooping Cranes are monitored at one-minute intervals for a minimum period of 30-minutes. These behaviors can range from foraging to social interactions (inter- and intraspecific) to being alert or defensive. Having a better understanding of Whooping Crane behaviors can help conservation organizations, such as the Crane Trust, determine the value of various landscapes. For example, research has found that Whooping Cranes consume vertebrates including frogs, fish, and snakes in river and wetland habitats, but forage on grains such as wheat and corn in agricultural fields. Documenting how often these habitat types are utilized will in turn allow for the Crane Trust to make better management decisions in regards to those landscapes based on their importance for the species. The Crane Trust wants to ensure that management decisions are being determined based on the needs of the species to guarantee the brightest possible future for one of the rarest birds in North America!

To learn more about the ecology of Whooping Cranes and how the Crane Trust manages the habitat that Whooping Cranes utilize, visit this link: https://linktr.ee/cranetrustwhoopingcrane

Until next time!

Cheers,

Amanda Medaries